The wonderful Peter Clarke has had two recent exhibitions

one in Woodstock and one in London...

Peter Clarke, 'Geisha', mixed media, 50 x 35cm, and 'Little Match Girl', mixed media, 50 x 35cm (2004). Courtesy of Stevenson.

Letter from Cape Town

Fanfare, rainbows & small miracles: Peter Clarke's Fanfare series is subversive in its joy -

An article by Stacy Hardy

"It is 30 degrees the day I visit the group exhibition Fiction as Fiction at Stevenson Gallery in Woodstock, Cape Town. On the street outside poverty and squalor, the banalities of heat and dust collide with the cool austerity, the polished glass and marble of a new multi-story, multi-venue mall; the elated confusion of city streets where the BMWs of the nouveau-rich inch their way between honking microbus taxis and throngs of sweating pedestrians; factory shops and designer outfitters; oil on the tarmac; air that smells of fried chicken, dust, exhaust fumes.

We’re like that here: always oscillating between poverty and wealth, the ultra-modern and the crumbling. Always tearing down and rebuilding history. The gallery itself is a converted warehouse space – a sparse room, total absence of natural light, whitewashed walls – that provides its wealthy urbane audience with a retreat from the contested terrain of property, race, ownership and change outside its doors.

Perhaps it is the cool austerity of the space that instinctively draws me to a series of vibrant, wedge-shaped designs that fill one wall of the gallery. These unashamedly joyful, fan-shaped collages are part of artist Peter Clarke’s Fanfare series. As its title suggests, Fanfare is a celebration that delights in delighting its viewer with surreal images, bright colours, sharp turns and sudden outbursts. But it is not just the act of creation that Clarke is celebrating here. In a clever slippage between artist and subject, creation and creator, he presents himself as a fan: an admirer, an ardent follower, paying tribute to the historical, biblical and literary figures, as well as ordinary people that have inspired him during the course of his epic fifty-year-long career.

Completely self-taught, Clarke refuses to set any boundaries for the artwork and employs a deliberately low-tech approach in response to the increasing popularity of conceptual media of expression and high production values. He uses found pages torn from discarded books and magazines, as well as a variety of media, including pen, marker, paint, crayon, ink, all layered on top of each other to craft images that echo the complex layers of culture on the street outside.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, the project has elicited little fanfare from art critics here in South Africa, where it has been critiqued as “arty rather than art”; “prosy rather than profound”. This reading is accurate but disingenuous. Yes, Clarke’s works are craft-driven but they are also crafty; small and whimsical, sure, but also large precisely in their small whimsy.

Without fanfare, in the simplest way, Clarke approaches the unaccountable in small measures that draw us down to a whole other kind of immensity. Despite his age (over 80) his supremely quirky mind enables him to combine the strange and the familiar, bursts of poetic indulgence with found text to tap the mystery that lies folded below the surface of things and reveal a world filled with a thousand odd, small, jagged miracles.

Fanfare is, then, a journey through the “anti-miracle” of South Africa’s embattled past. It follows the lives of historical, fictional and semi-fictional characters (racketeers, artists, criminals, activists, kings, ghosts, fairytale princesses, friends, lovers cross and recross) to unearth and amplify small moments of almost impossible music, bravery, beauty and redemption in the face of tyranny and repression.

This microcosmic, fragmented vision presents a striking counter point to the failed grand miracle of South Africa as the “Rainbow Nation”. At the same time, the intense joy of Clarke’s rainbow works provide a subversive alternative to the increasingly cynical, bitter tone of so much South African art. In the face of pessimism, Clarke fronts catastrophe with loving eyes. Small wonder, then, that he found miracles!"

Stacy Hardy is a writer based in Cape Town. She is an associate editor of the Pan-African journal Chimurenga. Her writing has appeared in Donga, Pocko Times, Art South Africa, Ctheory, Black Warrior Review, Evergreen Review and Chimurenga. Her short film I Love You Jet Li, created in collaboration with Jaco Bouwer, was part of the transmediale.06 video selection and was awarded Best Experimental Film at the Festival Chileno Internacional Del Cortometraje De Santiago 2006. A collection of her fiction is forthcoming from Pocko Editions, London.

Have a look at Peter Clarke’s Fanfare series: www.stevenson.info/exhibitions/clarke/clarke.htm

An interview with Clarke talking about Fanfare: www.stevenson.info/exhibitions/clarke/essay.htm

Peter Clarke’s exhibition Wind Blowing on the Cape Flats also showed at Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts) in London until 9 March. www.iniva.org

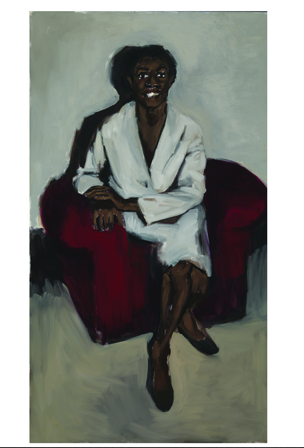

Peter Clarke ' Listening to distant thunder' (1970), oil and sand on board. © the Artist, courtesy: Johannesberg Art Gallery

Peter Clarke: Wind Blowing on the Cape Flats

16 January 2013 - 09 March 2013 /

Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts), London, United Kingdom

In partnership with the South African National Gallery (Iziko Museums of South Africa), Iniva presents this major retrospective and first substantial exhibition in the UK of Peter Clarke‘s work.

As South Africa prepares to celebrate 20 years since the election that brought Nelson Mandela to President, and with Jacob Zuma recently securing a controversial second term to lead the governing African National Congress, the show reflects on the nation’s social and political history through the work of internationally acclaimed artist and writer Peter Clarke (born 1929). Wind Blowing on the Cape Flats charts his development as an artist, his prolific creativity as a painter, printmaker and an internationally acclaimed writer and poet through over 80 works including paintings, drawings, prints, woodcuts, collages, sketchbooks as well as artist books. The exhibition honours Clarke’s life, work and contribution to art over sixty years, and tells the story of an artist whose sharp, poignant and aesthetically memorable work provides an extraordinary context for discussion of South Africa, apartheid and post-apartheid. Clarke has reflected on his country’s social and political history and is often referred to as the ‘quiet chronicler’ and has become an inspiration to many other artists.

www.iniva.org

Reblogged from